An all too familiar story for girls on the autistic spectrum reminds us that we can gain a lot from listening to others.

I have previously articulated some of the key issues schools need to keep in mind when supporting autistic girls, and I’m always keen to try to gain further insight into the challenges faced by young people and their families.

When one parent from another part of the UK offered to describe her experience, it was such a powerful message that I was instantly convinced others should hear it too. This is her story.

‘I often wonder whether anything could have been done differently at school to prevent my daughter being in her current situation.

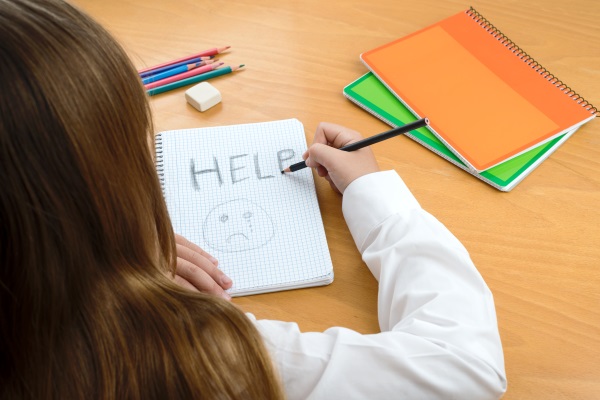

‘She is a textbook example of what happens to undiagnosed and late diagnosed high-functioning girls on the autism spectrum who go through the mainstream school system. A delightfully bright and happy pre-schooler became an unhappy but academically gifted and engaged primary school pupil, and in turn an isolated and disengaged secondary school student.

'Severe mental health difficulties, self-harm, disordered eating, suicidality and sky-high anxiety now mean that the only educational provision she is able to access is a few hours a week from the local authority home tuition team.

‘You often hear the mantra in education that schools don’t respond to diagnostic labels, they respond to children’s needs. That may well be the case with boys who display challenging behaviour in the classroom, but girls display their challenging behaviour at home, out of sight of teachers, and so it goes unnoticed.

‘The autism spectrum disorder (ASD) label is often the first hard signal to a school that accommodations need to be put in place to support the young person. When girls aren’t diagnosed, or are diagnosed late, and their challenging behaviour is hidden from view, they spend most of their school career unsupported. When they crash it can be spectacular.'

‘My daughter finally got her diagnosis at 14 following previous diagnoses of severe depression and an eating disorder. But from the start of secondary school, which was when she really started struggling, there were so many times when accommodations could have been made.

‘These were all signals and missed opportunities to respond to a child who was clearly struggling socially and emotionally despite excelling academically. She was left to fend for herself, and although was considered vulnerable, was not considered of high concern.

'It wasn’t until we secured the autism diagnosis and she was put on the SEN register that support and accommodation above and beyond the ‘usual’ pastoral care were finally made available. Unfortunately, by that point it was too late and her mental health had deteriorated so much that shortly afterwards, she ended up in a secure psychiatric unit due to acute concerns over her suicidal ideation.

‘My daughter’s issues were identified and highlighted, but just not as something that the school needed to address. These were issues for her parents, CAMHS and other agencies to deal with.'

‘I speak to many other parents with autistic girls in similar situations. Almost always, they requested greater intervention from schools, pre-diagnosis, when they saw the mental health of their children declining. But all too often, they came away feeling ignored, patronised, or even blamed for their child’s poor behaviour which was only apparent at home.

‘School staff need to be better at joining the dots and recognising the signals when students without challenging behaviour are struggling and need additional support. Schools also need to recognise that they are often the primary cause of mental health issues, but are absolutely vital in providing solutions.

‘My message to SENCOs is not to undermine, undervalue or disregard the vital feedback, information and strategies parents and carers can provide about their child’s difficulties, even if the child isn’t presenting these at school.

We had to reach a crisis point before a partnership was achieved

‘There often appears to be a lack of enthusiasm by schools to reach out to parents and to include them in decision making, tapping into their vast expertise and armoury of strategies that might help in the school environment prior to a diagnosis. This needs to change.

‘The best outcomes are achieved through collaboration and co-production, with schools recognising and crediting parents and carers as experts on how best to manage their own child, and using this vital knowledge to inform accommodations and interventions.

‘There are numerous low-cost social and emotional interventions that can be put in place for girls who are struggling pre-diagnosis. In many cases it isn’t money that is holding schools back from providing vital support to girls with autism, it’s schools’ lack of creativity in coming up with solutions and their unwillingness to bend relatively unimportant rules.

‘I have an excellent relationship with my daughter’s SENCO and we work very closely to support my daughter educationally and to try and reintegrate her into school. However, we had to reach a crisis point before this partnership was achieved, and my daughter has paid the price.’

There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that these powerful words portray a similar story for many young females and their families. I could not agree more that co-producing outcomes is essential, for any student, but especially so for autistic girls, diagnosis or not.

We need more specific training and a broader awareness in schools, and for a better understanding of how to work with the individual young people in understanding what autism means to them. I am reminded of the amazing review that Megan, one of our ex-students wrote of Tania A Marshall’s Aspien Girl a few years ago. I wonder if, along with strong home-school partnerships, peer support is also an essential element of high quality provision.

Whatever the specific need or diagnosis, the message is clear: we should always listen to and work alongside parents and carers. However ‘experienced’ we are, we can all learn more from the true experts.

Why we need more ethical SEND leaders

'On the back foot': a parent's view on choosing the right school for SEND

Autism: 5 books to add to your reading list