Teacher mental health has been a concern for over a decade, so why has so little been done to tackle the issue? John Viner shares the research around teacher stress, and why urgent action is needed.

Damian Hinds has recognised that if we are to retain teachers, something has to be done to address the things that are causing them to leave.

Not rocket science, you might say, but it’s much more than the two causes identified in the DfE’s 2018 study, Factors affecting teacher retention: qualitative investigation.

This study identified workload (no surprise there then!) and ‘a combination of other factors’, meaning, I suspect, the pressures of accountability, targets and Ofsted.

It’s right to identify a couple of areas to focus on, but this is so much more than that.

It’s about the whole job of being a teacher, and, increasingly, being a TA.

Ths isn't just an issue in England. I happened to be chatting to a primary teacher from Massachusetts last weekend and he was saying exactly the same things.

A good, committed teacher, he doubted he would be in the profession after the next five years. For what it’s worth, US teachers are even more poorly paid than those in the UK but, as the DfE study demonstrated, it’s not really an issue of remuneration alone.

The issue of teacher wellbeing is probably the single most significant factor in school improvement and, at the same time, the area that the government and schools have done least about. Study after study tells us how unhappy teachers are.

For example, a 2016 research paper by Judi Kidger et al states:

'It is widely acknowledged that teaching is a challenging job, and high levels of mental health problems are seen in this population. Our findings suggest that feeling stressed or dissatisfied at work is associated with poorer wellbeing and higher depressive symptoms.'

Yet, we also know from Briner and Dewbury’s 2007 study that there is a two-way relationship between teacher wellbeing and pupil performance. As the authors point out, ‘if we want to improve school performance, we need to start paying attention to teacher wellbeing.'

So, why is it that, a dozen years on from this study, we are:

It really does the government no credit that its mental health plans for students do not come to fruition until 2025, and that little has been done to change teachers’ working conditions. If teachers are to be expected to support their pupils’ mental health, then it stands to reason they their own mental health is safeguarded.

Perhaps, despite the warnings, it is because we have been too busy in schools working around the high-accountability measures that drive our strategies. Perhaps we have focused too much on the outcomes and too little on the people tasked with achieving them.

There is a two-way relationship between teacher wellbeing and pupil performance

Similarly, the DfE has recognised the problem of teacher recruitment and retention, but it has been slow to react to the forces that make teachers leave early. Figures tell us that even long-serving career teachers are now less likely to continue through to retirement than they were a decade ago.

These early signs that teacher stress is being taken increasingly seriously and the current media interest in mental health are encouraging, but we need to find solutions for how we tackle teacher stress now.

For two years now, the charity, Education Support Partnership has published the Teacher Wellbeing Index. The most recent index was released in October 2018 and, unsurprisingly, the results revealed what an arid landscape exists in England’s schools.

Action to support teachers’ wellbeing is moving up the agenda. But we cannot wait for the DfE to introduce measures for schools to follow.

It's more pressing than that.

Amanda Speilman may be shifting Ofsted away from an over-emphasis on standards and progress, but we have yet to see what difference that makes.

Schools are caught up in a long-established culture of chasing results and focusing teacher performance on securing progress. The impact on staff is evident, the impact on schools is seen in their recruitment difficulties and the impact on the education service is an annual shortfall of some 20,000 teachers.

Some schools and local authorities are putting wellbeing measures in place. The following blog will consider practical steps that schools and teachers can take to bring about change.

Right now, the very least school leaders could be doing is taking the wellbeing of their staff seriously at every level.

Carry out a quick audit. Find out what keeps your staff awake at night – what is adding to their stress?

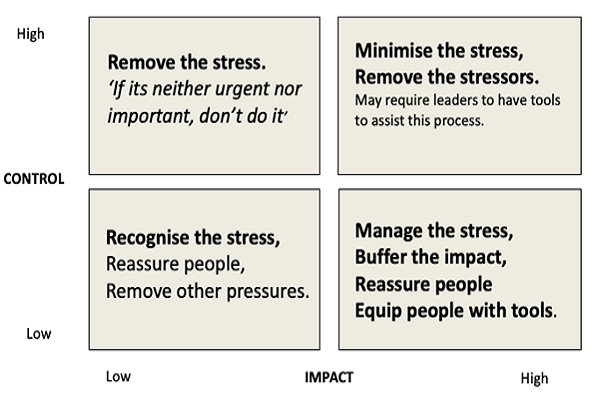

There are two axes here; their impact and your control.

As the diagram above shows, it’s like the urgent nor important box.

This may help you to take some immediate action. In the follow-on blog we will look at more detailed solutions.

The final comment comes from the Teacher Wellbeing Index.

'As a society, the need for clear measures that protect the wellbeing and mental health of all has never appeared more urgent. In education, it is becoming critical.'

If you think that you need urgent mental health support, then call the Education Support Partnership’s free helpline on 08000 562 561