Parents have a right to choose to educate their child at home and may do so for several reasons. With little regulation and lack of clear guidance, John Viner explores the role schools, local authorities and parents play.

As a headteacher it always troubled me that parents can withdraw a child from school at almost any point, claiming that they are educating them at home, as is their right.

While some parents may have very good, sensible reasons for this decision, and also have the capacity to home-school them at an age-appropriate level, there are always those who withdraw their child to avoid prosecution for non-attendance or who fear that their child will be given a label that will disadvantage them.

One such was Martin, a Year 5 pupil in my school who had serious and escalating behaviour issues as a result of being on the ASD spectrum.

We were doing really great things with him, helping him to build relationships, read social cues and develop coping strategies. As a result, he was making decent progress and had the potential to do well.

Suddenly, mum told us she was going to educate him at home. He left the school, fell off the radar and I have no idea what happened to him after the family moved away.

Ofsted have recently reported on this, suggesting that special educational needs, medical, behavioural or other wellbeing needs were the main reasons behind such a move for parents and their children.

Sadly, the report also noted that there was little or no discussion between school and parents before the child moved, and little consideration was given of what was the best outcome for the child. Ofsted also found that, in some cases, the process of making the move can take less than a day, as it did with Martin.

Ofsted will look very closely if there is evidence of a school ‘off-rolling’ difficult pupils and it would always be a bad idea for a school to ever suggest, whether in writing or verbally, that home education was the best choice.

It would always be a bad idea for a school to ever suggest, whether in writing or verbally, that home education was the best choice

Once a pupil has been removed for home education, they are no longer on the school’s roll. Schools must immediately inform the local authority because they have a responsibility for identifying children in their area who are not receiving a suitable education. However, LAs do not currently have any formal powers to monitor the education such pupils are receiving.

In some case, of course, schools will need to inform social services since sometimes these ‘under the radar’ pupils may be at a higher risk of harm. In addition, although some local authorities operate voluntary registration schemes, there is currently no legal obligation for a parent to register or inform a local authority that their child is being educated at home.

Because it is a parent’s legal right to home-educate their child, Ofsted has published the Elective Home Education guidance. Schools should know about this guidance and ensure that any parent considering this step has access to a copy.

There is no obligation for parents to aim for the child to acquire specific qualifications

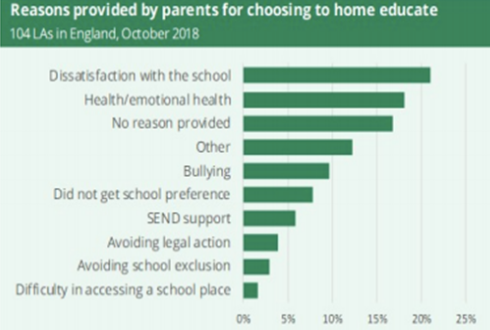

This document includes the reasons why parents choose to home-educate – an awareness of these reasons my help schools to identify the pupils at risk and begin working with homes and families to head-off withdrawal.

DfE guidance recommends that parents provide their child with ‘efficient’, full-time and ‘suitable’ education but there is no legal definition of any of these terms. Additionally, there is no obligation for parents to aim for the child to acquire specific qualifications, or to provide a broad and balanced curriculum.

Elective Home Education Survey: 2018, ADCS

Recently, parents have been given the right to request ‘flexi-schooling’, working in partnership with the school. However, there is no obligation on schools to accept such a request.

If the local authority has reason to suspect that a child is not receiving a suitable education, it may make informal enquiries with the parents. If this does not resolve the position then, under section 437 of the Education Act 1996, the local authority must serve a notice on the parents requiring them to satisfy the local authority within a specified period that the child is receiving a suitable education.

If a notice is served and the authority is not satisfied then it will, under section 437(3) of the Education Act 1996, serve a school attendance order requiring the child to become a registered pupil at a named school. The parents can be prosecuted if they do not comply with the Order. All this takes time and, meanwhile, a pupil’s education may suffer.

Where a child has an EHC plan, the LA has a duty to ensure that the educational provision specified in the plan is provided. But this only applies if the parents have not arranged for the child to receive suitable education in some other way.

Where the EHC plan names a school and the parents decide to educate them at home, the LA does not have to make the SEND provision set out in the plan, as long as it is satisfied that the arrangements made by the parents are suitable.

There are organisations that exist to support home educators and the support they provide is often excellent. However, this is effectively independent education without school fees. Not all parents are able to meet the consequent financial implications of buying into the service.

The most well-known and helpful player in this field is the charity Education Otherwise. They offer support, guidance, a telephone helpline and help to organise local EQ groups.

Home education remains contentious and, while currently subject to little regulated control, the DfE has recently consulted on proposals to create four new duties.

None of this has yet found its way into legislation but things could change.