Your plan for school development need not be the most unwieldy tome or a way to impress those who hold you to account. John Tomsett explains how you can focus on what matters.

Less is more, always. School leaders invariably feel safe when we have lots of plans to demonstrate the efforts we are making to improve our schools. In the past I have been horribly guilty of thinking more is more!

Sir Tim Brighouse’s largely unheralded Essential pieces 'booklet' (his [editor’s] word, not mine) is a sharp, pared down guide to The jigsaw of a successful school. Few people talk as much sense as the Knight of the Realm, Sir Tim Brighouse. School improvement is not hard as long as you keep it simple and focused on what matters.

The jigsaw of a successful school is sharp stuff and required reading; it embodies the principle of keeping things coherently simple. In his introduction he makes the following observation about school improvement:

'…whenever I’ve visited a school, which has recovered its sense of direction and pride after falling on hard times…I ask the (usually new) head teacher, “Well, what did you do?” The reply is always the same. Whatever the headteacher’s style, whether understated and calm, cool and determined or outrageously busy, the reply usually contains the phrase: “Well it’s not rocket science. We just concentrated on getting a few essential things right”.'

'...getting a few essential things right.' Just let that sink in. Then ask yourself as a leader in your school whether you have ever deliberately produced a thicker-the-better development plan, in order to show:

Have you thought 'more is more' at some point in your career? I certainly have, more often than I care to admit.

As a headteacher, my first school development plan was a beast, only portable by supermarket trolley. When I presented it to the governing body the meeting was on the first floor and my PA Rita and I, with 20 copies of the thing to carry, had to take the lift. It was 74,000 words long and had 38 development initiatives.

I wasn’t interested in getting a few essential things right. I wanted to get everything right straight away.

That governors meeting where I presented my first plan (of course it was mine – I had to prove myself as a headteacher and there was no way anyone else was going to tell me what to do) lasted until 11.30pm.

Not only did I circulate hard copies of my school development encylopaedia (SDE), I also had 127 PowerPoint slides (mostly text copied verbatim from the SDE itself) at my disposal to help explain to governors what we were going to do over the next year.

It was great. I loved it. I gained some odd satisfaction from the strain and pain of giving birth to the thing, the weekends spent typing the beast up whilst my wife and kids entertained themselves; an absent father in the next room. And I had no idea how I was going to measure whether what I had planned had worked.

Looking back now, it’s embarrassing to think of that first development plan. Luckily, I had a seasoned headteacher to show me there was another way. Kerin Rees had just retired from headship and the local authority asked her to be my mentor. The LA knew me better than I knew myself.

Kerin reined me in and helped me reduce the SDE to an SDP, with just five development strands – three strategic and two operational:

Strategic objective 1: raise the standards of learning and teaching.

Strategic objective 2: develop a modern provision for all our learners.

Strategic objective 3: develop a highly effective self-evaluation system.

Operational objective 1: develop a highly effective CPD programme for all staff.

Operational objective 2: target resources efficiently upon raising standards throughout the school.

All well and good, but even then I had 18 different initiatives beneath these five objectives. The thing is, it really is difficult for a new headteacher – any headteacher – to think clearly and prioritise with ruthlessness.

I had no idea how I was going to measure whether what I had planned had worked

It depends where you are in the development cycle of a school, but wherever you find yourself on the development cycle, pare down your priorities and do a small number of things really well. Easier said than done. In the past I have battered SLT and staff with Year 11 intervention plans that are hundreds of pages long.

A culture of fear breeds backside covering. It's really easy to implement extensive interventions to raise headline results figures just so that you can point to how much you did to improve results when the results turn out to be disappointing in August. 'I know the results are rubbish, but we worked really hard – look at all the things we did…'

It's easy to think that 'more is more' and you need to get everything right straight away

The trouble is that, as headteacher, the buck stops with you. Chris Bridge, my boss when I was a deputy headteacher, identified the gulf between being a deputy and a head. He said to me that, as a deputy head, I could always go home and sleep at night because, ultimately, the buck didn’t stop with me.

Sion Humphreys from the National Association of Head Teachers had it right, when he said in 2013:

'For headteachers, you're only as good as your last set of exam results. For the vast majority of teachers and school leaders the motivating factor is to make a difference. It's a cliché, but it is what gets people out of bed in the morning. But, increasingly at the back of their mind is also: 'I have a family, a mortgage, a career and aspirations.'

When things go awry, try to hold your nerve. When I inherited Huntington in 2007, with its reputation as a high-performing school, it had just attained its best set of GCSE results with students attaining 59 per cent 5 A*-C grades including English and mathematics.

In 2010, three years into my headship, when the results dipped to 55 per cent 5 A*-C grades including English and mathematics, we had had the most intensive Year 11 raising attainment plans (RAP) for English and maths ever. No strategy was left unemployed!

We were doing nothing but developing learned helplessness in our students

Our Leading Edge consultant thought our (RAPs) highly impressive when she visited in the June. In late August, a young Leading Edge researcher e-mailed me wanting to feature our RAPs in his Leading Edge Next Practice Showcase publication, having read the consultant’s rosy-sounding report. I told him not to bother because they hadn’t b****y well worked! For all the frantic effort, our results had fallen 5 per cent since 2009!

What I didn't write in that post was how, on that damp August results day, I sat in my car as the rain pummelled down on the roof and I wept. I felt like the loneliest man on the planet.

I finally rang my wife, who said to me 'John, come home. We all love you. You can pack it in. It's really not worth it.' Her words were the balm I needed just at that moment, but like Sion Humphreys says, I have a mortgage.

As a school we held our nerve back in 2010. I stopped most of our interventions. In January 2010 we had mentored all the Year 11 students we’d identified as underachieving.

One of them said: 'We are looking forward to all the extra revision lessons you're going to put on and you making us go to them.'

It was at that point that we realised that we were doing nothing but developing learned helplessness in our students. We stopped doing many of our interventions and began pouring our resources into a couple of things that our evaluations said had worked.

I removed the disengaged Key Stage 4 students from their English classes. I co-taught the Year 11s with the deputy headteacher, and I taught the Year 10s on my own. This helped all the other teachers and got me back at the heart of teaching again.

I put teaching first. We changed the structure of the school day so that every other Monday we have two hours CPD, as well as our five training days. We invested in CPD. We stopped anything that sapped teachers’ energy; this allowed them to teach great lessons during the school day. The students were told there was nothing else but the lessons, so they made the most of them.

Ultimately, the day-in, day-out dedication of our teachers and support staff is at the root of our improvement since 2010. Since 2010, we have got better and better and were finally judged to be Outstanding by Ofsted in October 2017.

Alex Quigley wrote brilliantly about why it is so difficult to drop your raising attainment strategies. In his article, Are gimmicks and trends getting in the way of teaching?, he makes the point that 'we should analyse what tools we could and should throw off to lighten the load, allowing us to respond flexibly to what matters – teaching and learning.

'Anything that distracts teachers and school leaders from improving teaching and learning are cumbersome tools that serve only to weigh us down.'

Like Quigley, I think it is really important that we ask less of everyone in schools; when I say less, I mean reduce to the bone what we all need to do so that everyone single one of us can concentrate on making our teaching as good as it can possibly be. It follows that if we are asking less of people, what we do ask for has to be of an excellent quality.

Institutional coherence only comes if you can study the flight of your ball, not just your swing

Institutional coherence in schools stems from the accurate interpretation of your students’ performance. John Jacobs, one of the greatest ever golf coaches, used to say that the best way to interpret what was happening with your golf swing was to study the flight of your ball when you hit a shot.

The parallel with teacher improvement is perfect – a forensic analysis of our students' results using all the intelligence available (and with the examination boards' online post-results services, combined with our understanding of the combinations of flesh and blood that produced those results, and copious amounts of our own wisdom and judgement, we have all we need) is a great source of evidence for understanding how we need to modify our teaching to improve our students' performance.

You need to train teachers to be data rich and intelligence rich

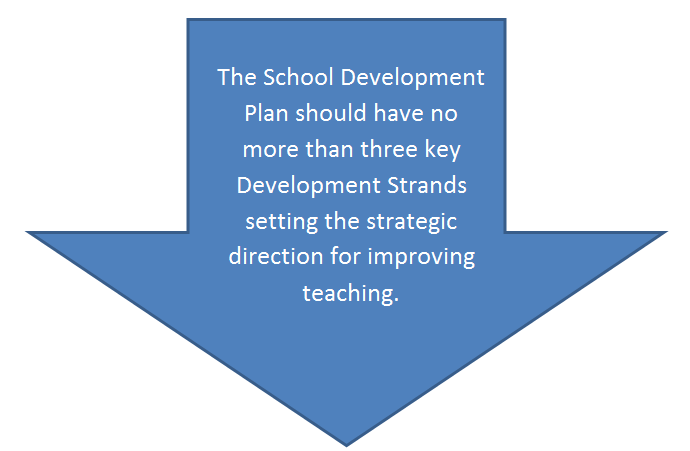

Keep the key processes of school improvement aligned. Begin by setting the school's strategic direction for improving teaching. At the moment we are working with a school development plan which has two wholly coherent central development strands:

Then set a mid-term strategic overview, but monitor and evaluate annually. Once the strategic direction is set for the next three years, undertake, on an annual basis, an accurate interpretation of the examination results at school, department and individual teacher levels.

Act upon your findings in a very measured, focused way:

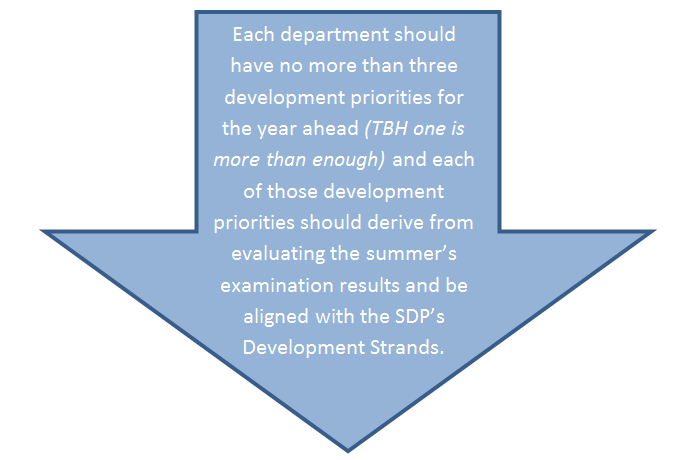

Once you know what you need to do, don’t be diverted. All the departmental development meetings for the year will focus upon the (no more than) three development priorities. Do the administration some other way and keep your teams focused upon the collaborative development of teaching skills.

Every department can engage in the analysis without it being a burden. You need to train teachers to be data rich and intelligence rich. Once they have undertaken their department’s analysis of their students’ performance they can weave their plans for the coming year into the whole-school development plan.

You cannot just wish teachers to be better. Once you have identified the focus for development, subject by subject, you then have to provide the conditions for growth within the school.

It’s about the culture, as I explained in my book Love over Fear: This Much I know About Creating the Culture for Truly Great Teaching.

This is the final installment in John's series, 'From vision to action'. Follow the links below for the posts you missed:

1. Developing your school's core purpose

2. Establishing a vision for your school

3. Choosing your school's values

Optimus Education's MAT Leadership Programme will provide you with the skills needed to drive change and improve outcomes across your multi-academy trust (MAT).

This series of six one-day modules is ideal for any member of a MAT leadership team.