The secrets of high-performance organisations aren’t that secret - and may not be that useful in education.

Everyone loves a success story, and schools are no different. Little wonder that the smouldering trails left by some high-performing businesses, whether Google or Apple, seem to appeal to school leaders.

In Joe Kirby’s post on the culture of Netflix he asks us to imagine working for a school run on similar lines, ‘where every person you work with is someone you admire and learn loads from’. It’s hard to disagree: who wouldn’t want to work with high-achieving, smart colleagues, especially when culture clearly matters for school success?

But culture is built on a bigger foundation, and a less exciting one: context. Culture for schools and Silicon Valley has to be different, because their goals are radically so.

So, let’s take a dive in and see what we can learn from companies that have travelled from tiny startups to culture-defining giants.

Point 1 is this: these high-growth organisations focus relentlessly on talent. Part of the appeal of a strong culture is that it allows you to attract the best people, who in turn reinforce that culture.

In How Google Works, Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg paint a picture of success that is predicated on people. Instead of strategic business plans, they argue that companies should be organised around ‘smart creatives’, and build a culture that lets them get on with things.

You hear the same thing from Hubspot, a marketing firm, who argue that ‘culture is to recruiting as product is to marketing’, or Spotify, quoting Jim Rohn: ‘you are the average of the five people you spend the most time with’.

At the extreme end here is Thread, who kept a vacancy open for over a year – just because they couldn’t find someone who was truly exceptional to fill it.

There are two lessons for schools here: one good, and one bad.

The good is that an organisational culture that focuses on success, and is built around the people in it, tends to attract exactly the people who you would want to take part. Most of the high-performing schools I’ve visited have something distinctive about their vision that draws in ambitious, demanding teachers.

The bad is this: the tactics of companies aren’t easy for schools to follow. Schools have responsibilities startups don’t, not a least a requirement to get teachers in front of pupils. Even if schools commit to hiring the best, in a time of recruitment difficulties just finding a good maths or physics teacher can be a challenge.

With too few teachers coming into the system, schools often aren’t in a position to hold out for the perfect hire – and the means to allow this, such as pushing up class sizes, aren’t especially palatable.

Geography comes into play too. It’s easy for a tech firm to locate itself in California and hire the talent from Silicon Valley. Schools have to be where pupils are: that is, everywhere. And it is often in precisely the areas where great teachers are needed the most – challenging coastal towns, say – that it is hardest to recruit them.

And there’s one more very ugly flipside here.

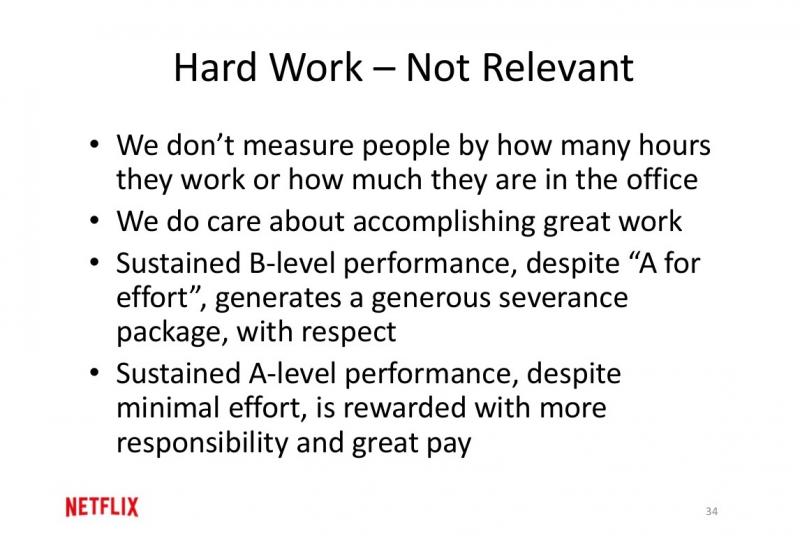

If you’re truly committed to recruiting high performers, and think you can reliably identify them, you have to let the worst performers go.

This is most brutally evident at Netflix, where effort or loyalty to the company doesn’t matter – if you’re not a high-performer, you go.

This seems to work for Netflix. But such approach requires you to have absolute confidence in your ability to judge high-level or low-level performance. And where it might be easy to judge the impact of a software engineer, by the code they write or the products they ship, assessing the value of teachers is not nearly so easy.

While we know the effect of a good teacher is much larger than that of a bad one, it’s also incredibly difficult to evaluate teacher performance in any sort of credible way. At its worst, a haphazard commitment to firing low-performers could just lead to firing teachers who don’t teach like you: not necessarily a sustainable path to improvement.

A final point here. At any given time, there are only so many people qualified to teach. As Dylan Wiliam argues, dismissing teachers generally just results in them teaching somewhere else: choosing to fire someone keeps the net improvement for the school system at zero.

To improve schooling, investing in teacher development might prove a better option than teacher dismissal.

Another value leaps from the pages of these companies’ culture manifestos: customer focus. Their watchword is relentless focus on fixing the problems that matter for users.

For Hubspot, this is about ‘solving for the customer’, prioritising the user over any internal manoeuvring. At LinkedIn they call this ‘transformation of world’: a fancy way of stating their ambition to reshape the global job market.

The point is that across these companies the focus is kept firmly on the value the companies can deliver to the customer – which is what it should be.

We're on the right path as long as we sell to customers that we expect to delight

Who is the customer for schools? Presumably it’s the pupils whose lives you are ultimately attempting to affect. And clearly no education expert is likely to deny that a rigorous focus on pupil outcomes tends to benefit schools.

There’s a difficulty here, though: it’s often not pupils who are the most demanding customers. Parents, senior leadership, external organisations (whether Ofsted or, more often, the spectre of Ofsted) can make demands on teachers that pupils won’t. Schools have conflicting interests which companies don’t: when profit is your goal, things are simpler.

This motto is lifted from the early days of Facebook, and strikes a chord with many of these firms. ‘How Google Works’ puts the context better than I could: ‘when technology is transforming virtually every business sector, barriers to entry that have stood for decades are melting away’.

Simple proof of concept: think of what Uber has done to taxis, Just Eat to takeaways or Netflix to TV.

Speed is crucial for businesses aiming to transform the world – you might be smaller than established giants, but you can move faster.

I’m not sure schools should aim to be disrupters in the same way. Teachers know in January exactly how many lessons are left until July. Pace is the wrong metric: what matters is the quality of those lessons and what pupils get out of them.

'Slow down and do things better' might be a better motto for schools.

I want to finish with a simple story to illustrate the chasm between company and classroom cultures.

In April 2011, Evan Spiegel, Reggie Brown and Bobby Murphy were sitting on the back of a failed business called Future Freshman, an app to help college applicants. Then they had an idea which seemed better: an app to send photos that you knew would be temporary.

In July 2011 a first version of what was then ‘Picaboo’ launched. By the end of that summer it had only got to 127 users - so far, so familiar for Evan and co.

But fast-forward a little and things started changing. In April 2012, Snapchat hit 100,000 users. By the end of 2012 it reached 1 million users, and 100 million in May 2015.

In March 2017 Snap Inc went public, making its founders some of the youngest billionaires in history.

This is the dream that keeps a lot of startups going, through the late nights and early mornings, chasing growth curves like this one.

What Snap illustrates is simple: for high-performing organisations, the name of the game is extremes. With outsize rewards like that of Snap’s on offer, the culture of organisations chasing these goals tends to equal extremes.

For schools it’s a little different. The stakes are higher in some ways: teachers directly and profoundly affect young people’s lives. But there are 8.56 million pupils in English schools, and they all need to be taught – well, ideally.

In the cutthroat world of tech it’s ok to have a few very big winners and a lot of losers. In schools you need cultures that are sustainable as well as speedy, and can help to improve teachers as well as hire the best.

If a startup fails, the only ones affected are those involved in it. If a school struggles, it affects all the pupils that ever pass through its gates. An oft-heard Silicon Valley mantra is to ‘fail fast and fail often’. But in the school system, unlike the free market, we want everyone to be a winner.